Sections

The Division Bell

[avatar user=”malm” size=”small” align=”left” link=”file” /]

“Life … is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.”Macbeth (ActV, Scene V)

Quantity Theory

The shockwaves and reverberations from Brexit continue to be felt around the UK and the world this week. Buzzfeed tried to summarize the frenetic crazed developments in the political aftermath in their own inimitable fashion and for once their hyperbolic tone didn’t sound exaggerated. The referendum served as a national division bell in a very literal sense:

Britain’s poor and workless have risen up. And in doing so they didn’t just give the EU and its British backers the bloodiest of bloody noses. They also brought crashing down the Blairite myth of a post-class, Third Way Blighty, where the old ideological divide between rich and poor did not exist, since we were all supposed to be ‘stakeholders’ in society. Post-referendum, we know society is still cut in two, not only by economics but by politics too. This isn’t just about the haves and have-nots: it’s a war of views.

Certainly the country continues to feel at loggerheads with itself:

This post in The Conversation attempts to frame the depth of “Palaeolithic passion” aroused in voters in terms of evolutionary psychology. Specifically, how each side had very different conceptual frameworks for determining free rider identity in the EU setup:

the Brexit vote goes far beyond the tribalism of everyday politics. By channelling the tragedy of the commons, it taps into many of the Stone Age emotions that evolved to make cooperation possible. And because every participant in the debate can be framed as a free rider by another participant, these emotions are amplified to the maximum degree.

The realisation that voters saw things differently depending on where they were on the inequality is explored in this piece looking at the result from the perspective of behavioural economics taking in Daniel Kahneman’s work around optimism bias, prospect theory and overconfidence which are all called out as key reasons why Leave proved attractive to so many:

as inequality increases, our perception of what’s fair becomes more unequal. That causes people to accept inequality. This is an example of a wider cognitive bias – the anchoring effect. … What’s going on here is a concern for relative status. People try to preserve their self-image by holding others down. This is entirely consistent with attacks upon immigrants and benefit claimants.

Tim Harford suggested a ‘quantity theory’ angle on proceedings in which EU membership was viewed as a zero-sum game in which every power gained by Brussels was ‘deducted’ from the UK. It’s a framing that echoes the “good begets good” heuristic introduced in the previous link. The Leave logo brilliantly conveyed this conflating one “good” act (“Vote Leave”) with “good” consequences (“Take Control”):

Many people who voted to leave did not see EU membership as a joint project for mutual benefit but as a zero-sum game that Britain was losing and Brussels was winning.

Whatever the rationale (or should that be irrationale), the fractured post-Referendum terrain is not promising in terms of social cohesiveness. Tensions may abate in time but in the backdrop of societal division, the huge challenge of dealing with the consequences of Brexit remains in wait for many years to come and our government hasn’t begun to start on this difficult and unglamourous part yet:

If Brexit goes ahead, it will take equally extraordinary leadership to steer the economy through its impacts, and to negotiate new trade deals with an unforgiving EU and other countries.

Winners and losers

Continuing the theme of balancing loss and gain, it’s instructive to try and understand who has lost and gained. Business confidence has definitely taken a serious knock and will take time and greater certainty of outcome to rebuild.

Millennials have found themselves the butt of various generalised put-downs and goads to ‘suck it up’ which will no doubt serve to stiffen their resolve and that of their progeny to vote Join in a possible post-Singularity future. If anything, Brexit has clearly shown that the future is plastic and can be remade with sufficient national will. Meantime the gap between young and old has formed another bitter faultline in British society and one that will need careful attention to avoid further fissure over the coming years.

Elites got a pasting from Nassim Taleb in a wild rant in The Express reprising one of the central themes of his well-known book, The Black Swan, namely the ‘ludic fallacy’ to describe the situation where experts fail to distinguish reality from a model and end up blindsided by outliers. But it’s a dangerous path to denigrate all experts all of the time. That’s the sure path to illiberalism.

Simon Jenkins in the Guardian also saw the result as an example of ‘creative destruction’ and force for change even if it meant taking the City and inflated house prices down a peg or two:

For all the talk of a widening gulf between rich and poor, the favour shown to banks and foreign money is astonishing.

It’s well and good of course to offer picaresque broad brushstrokes, but we are yet to see what emerges from the smoke. It may well be an even more brutal form of capitalism unbuffered by EU protection. Certainly the City has shown itself highly capable of protecting itself down the years weathering a whole range of would-be existential crises. For academia, however, the implications are stark and more near term as EU funding may begin to dry up well before we work out what replaces it.

Still, at least events apparently ended the ambitions of a number of politicians right across the political spectrum in what some dubbed “the Westminster Chainsaw Massacre” including the remarkably toxic ‘political serial killer’ that was Michael Gove. This erstwhile Macbeth v2.0, high puppet of the media barons was ultimately undone by clumsy text message:

To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Tech

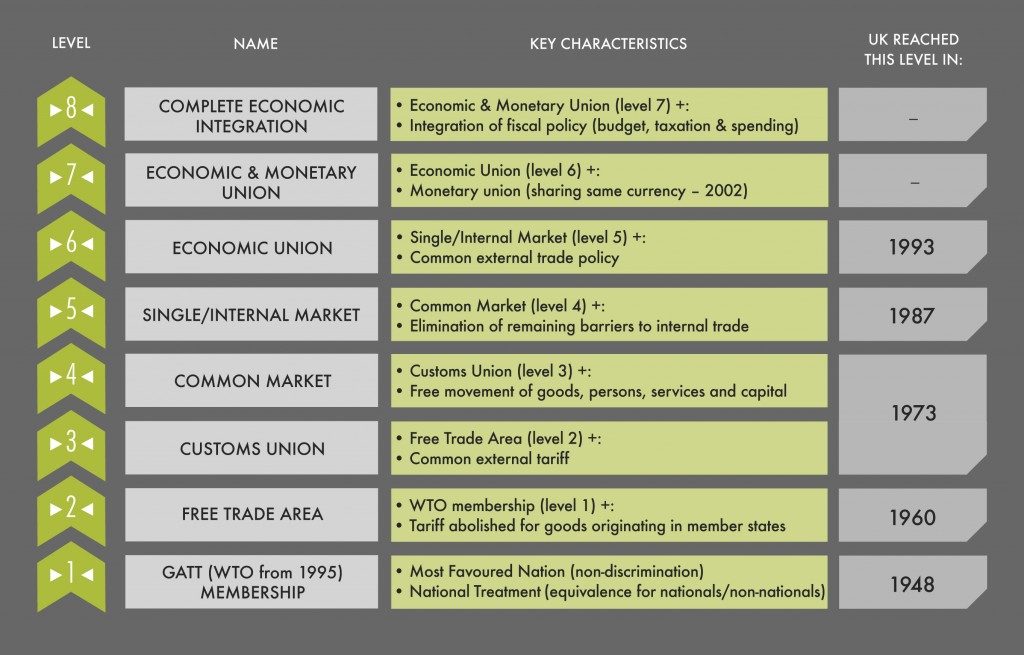

Most commentators see Brexit as bad news for the UK tech sector. Kemp IT Law provided a good introductory analysis of the option landscape the country faces post Article 50 which helps explain some of the key issues. Currently Britain is at level 5 in the “EU escalator”. We’re going down in terms of integration but where will we get off? Kemp argue that the lower down we get off the more challenging the environment for UK tech/IT startups. It feels like we voted for something between level 1 and 3. Curtailing freedom of movement of EU nationals is bound to damage a UK tech sector which relies upon access to a cross-EU labour market for talent. Decades of under-investment in UK education have left the country short of the engineering talent needed to sustain our needs and laudable though they are, grass roots initiatives like Code Club are not going to fill the gap. And yet it is clear that freedom of movement cannot be retained – doing so will be politically unacceptable.

Another area of concern for tech is the UK status post Brexit on data privacy. The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) ratified in April were designed to present a unified cross-EU position on this vital topic in an age of mass-scale surveillance. GDPR is widely seen as the gold standard, the toughest regulatory stance in the world:

Europeans will be able to tell companies to stop profiling them, they’ll have much greater control over what happens to their data, and they’ll find it easier to launch complaints about the misuse of their information. What’s more, the companies on the receiving end of those complaints face serious fines if they don’t toe the line.

Leaving the EU does not mean we can ignore them. Businesses providing digital services accessible in the EU (ie. everyone) will be required to adhere to GDPR. So what, in practical terms, does “take back control” mean in that context? Will the UK have its own local regulations to comply with on top of GDPR or not? Kemp IT Law are in no doubt that we don’t have much actual control to exercise on data protection:

In our view, adherence to EU data protection principles identical or similar to GDPR post Exit Day is a vital to the continued success of digital UK business and the UK digital economy.

It’s a sentiment echoed by Chris Pounder in this excellent analysis. Fashionable as it is to ignore experts these days, we need to understand as a nation that our post-Brexit stance on GDPR and a whole host of other areas relating to digital services is something we have to get right. Otherwise we risk digital recession as a result of losing out on the sunrise tech growth areas of the future and the jobs they entail. Many people who voted Leave perhaps had little comprehension or interest in the impact of their vote on our future prospects in a digitally interconnected world which simply did not exist in the pre-EEC days many older voters seem to want to go back to. Exceptionalism has its own price, one paid in the currency of integration.

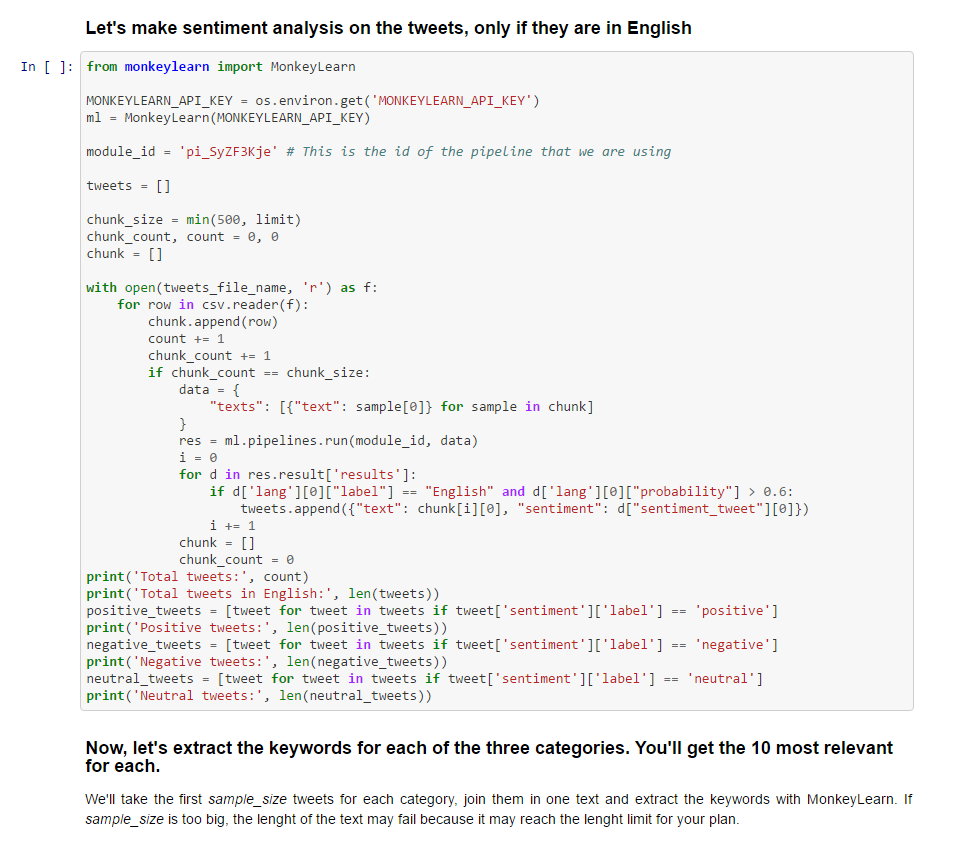

The final Brexit link this week is a fun one that combines another favourite topic of this blog, machine learning. This project on github uses the monkeylearn text classification web service to conduct sentiment analysis of tweets. It’s a nice zeitgeisty adjunct to the introductory text sentiment analysis approaches outlined a few weeks ago in the blog which used a combination of scikit-learn and spaCy:

Technological Unemployment

Staying with experts, for centuries, they have prophesied that machines would make workers obsolete. Now that long-predicted moment of mass technological unemployment may finally be arriving. This important Atlantic article surveys the landscape from the social benefits a job bestows:

Most people want to work, and are miserable when they cannot. The ills of unemployment go well beyond the loss of income; people who lose their job are more likely to suffer from mental and physical ailments.

sitting uncomfortably under the ominous shadow of automation:

The most-common occupations in the United States are retail salesperson, cashier, food and beverage server, and office clerk. Together, these four jobs employ 15.4 million people—nearly 10 percent of the labor force, or more workers than there are in Texas and Massachusetts combined. Each is highly susceptible to automation

For the author the solution is not universal basic income but a compromise in which we do less work rather than no work:

When I think about the role that work plays in people’s self-esteem—particularly in America—the prospect of a no-work future seems hopeless. There is no universal basic income that can prevent the civic ruin of a country built on a handful of workers permanently subsidizing the idleness of tens of millions of people. But a future of less work still holds a glint of hope, because the necessity of salaried jobs now prevents so many from seeking immersive activities that they enjoy.

Forbes have a different take on developments suggesting the future will be a life of “automated luxury communism”, an intriguing juxtaposition of words there and techno-utopianism in the extreme:

Robots, AI, machine learning, big data, etc. could basically make human labor redundant and instead of creating even further inequalities it could lead to a society where everyone lives in luxury and where machines produce everything.

The sentiments expressed above echo the positivist tone of a previous Atlantic post which didn’t explicitly mention universal basic income but that’s clearly the elephant in the Singularity room.

Given the concerns, it’s handy to know that McKinsey have exhaustively analysed the ‘automation potential’ of 2000 different types of work. The results are fascinating and clearly demonstrate that every job exists on a spectrum stretching between 100% automatable to 100% not. Rather than fixating on automation by job description, we need to analyse what an individual actually does:

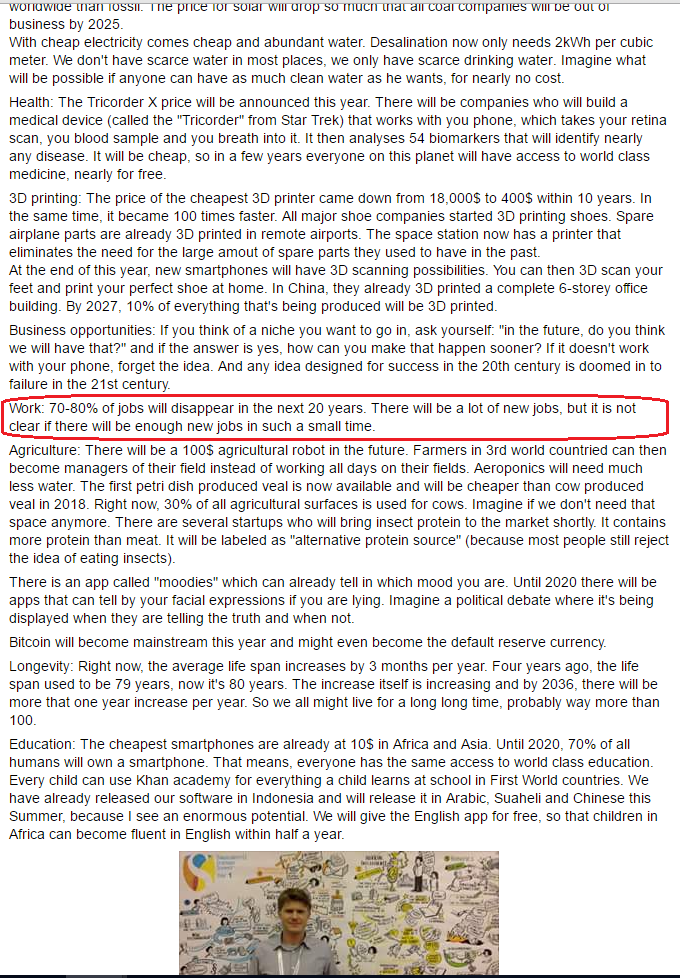

Udo Gollub’s notes of key learnings after attending the April 2016 Singularity University summit further underline the scale of disruption that is coming:

Artificial Intelligence

A “genetic fuzzy-based” AI called ALPHA defeated two attacking jets in a combat situation.

If that finally encourages you to get stuck in, then here are a great set of resources on “How to start Deep Learning”.

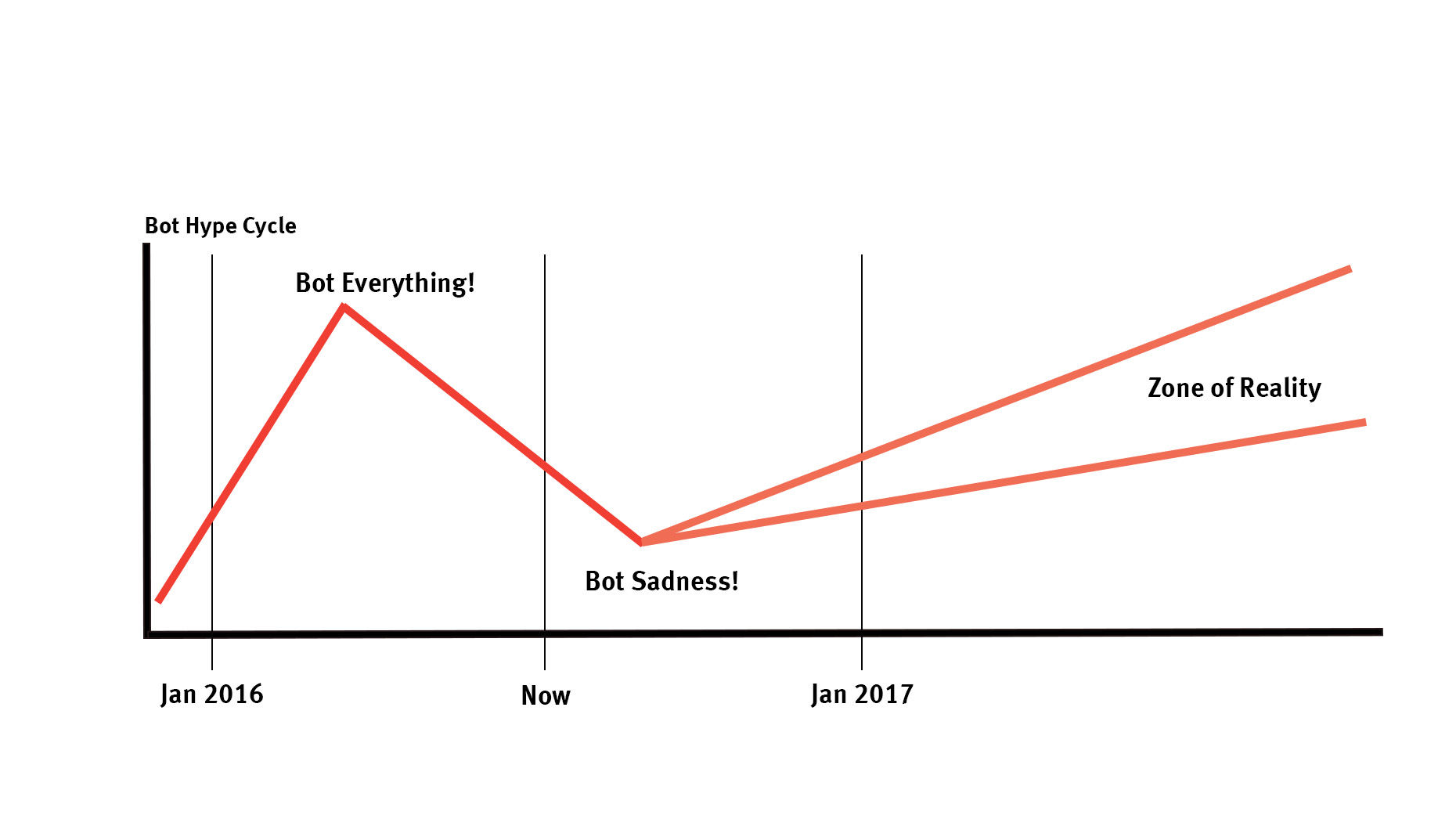

“State of the Chatbot Nation” round up from The Information suggests we are in the trough of disillusion or area of “Bot Sadness” in the bot hype lifecycle:

Big Data and Analytics

Bob Cringely has written an epic pair of articles exploring the origins, history and meaning of Big Data from a layman’s perspective. Part 1 covers mainly structured data from Stonehenge and the Domesday book up to dotcom era Amazon. Part 2 covers unstructured data, the rise of Google and advent of cloud computing:

Google will eventually have a server for every Internet user. They and other companies will gather more types of data from us and better predict our behavior. Where this is going depends on who is using that data.

Rob Charlton at Vertu interviewed by Computing on how operational data from handsets is analysed to improve software quality. It’s a great example of how an organisation can practically apply effective big data approaches today using commercially available tools like Splunk.

Other

The future for Chinese web freedom doesn’t look great with less room for free expression seemingly inevitable.

Can you solve the boat puzzle?